Welcome to the weekly roundup of great articles, facts and figures. These are the economic and financial finds that made our eyes pop.

Welcome to the weekly roundup of great articles, facts and figures. These are the economic and financial finds that made our eyes pop.

Where Do Jobs Come From?

Economist Jared Bernstein has laid out in simple, easy to understand terms, the theory of stimulating the economy to indirectly create jobs. This article is in reference to Uncle Ben's latest quantitative easing.

Let's talk about the process of job creation, both in normal times and in times like these.Demand for labor is so-called "derived demand," derived from the demand for goods and services that firms sell to consumers and investors. That can be anything from a Snickers bar (consumer good) to a steel bar (intermediate good) to barroom (investment good). As I explained in greater detail here, in normal times, job creation is a function of a virtuous cycle where growth generates income which drives consumption, signaling investors to new opportunities, generating more growth, etc.

But, of course, stuff happens and the cycle breaks down. There are big market failures, like the Great Recession. There are high levels of inequality that divert growth from reaching enough consumers to generate robust demand throughout the economy. There are inflationary supply shocks (e.g., an oil disruption) that sharply reduce real incomes.

When that stuff happens, monetary and fiscal policies are needed to reset the cycle and a key part of that process is avoiding layoffs and adding new jobs. So how does that work?

With the Fed, it works through lower interest rates. The Fed has a number of tools to lower the cost of borrowing, the idea being that this leads people to take out loans and make new investments that they wouldn't have undertaken at higher interest rates. And those new investments are associated with new jobs.

The punch line is a simple one, but it's one that seems to have been forgotten amidst our increasing love affair in America with laissez-faire economics: the more direct the policy measure -- i.e., the fewer links in the chain between the policy and the job -- the better it will work.

We said something almost identical in $2.6 trillion for 2 million jobs. The United States needs a direct jobs program.

Sixty-five Year Study Shows Tax Cuts Do not Grow the Economy

This is why Grover Norquist should be tared and feathers and run out of town on a rail. The Atlantic overviews how tax cuts don't cause economic growth:

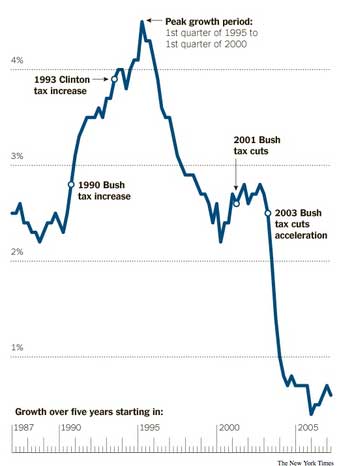

Here's a brief economic history of the last quarter-century in taxes and growth.

In 1990, President George H. W. Bush raised taxes, and GDP growth increased over the next five years. In 1993, President Bill Clinton raised the top marginal tax rate, and GDP growth increased over the next five years. In 2001 and 2003, President Bush cut taxes, and we faced a disappointing expansion followed by a Great Recession.

Does this story prove that raising taxes helps GDP? No. Does it prove that cutting taxes hurts GDP? No.

But it does suggest that there is a lot more to an economy than taxes, and that slashing taxes is not a guaranteed way to accelerate economic growth.

Guess what tax cuts for the rich really do? Why increase income inequality of course.

Analysis of six decades of data found that top tax rates "have had little association with saving, investment, or productivity growth." However, the study found that reductions of capital gains taxes and top marginal rate taxes have led to greater income inequality. Past studies cited in the report have suggested that a broad-based tax rate reduction can have "a small to modest, positive effect on economic growth" or "no effect on economic growth."

Well into the 1950s, the top marginal tax rate was above 90%. Today it's 35%. But both real GDP and real per capita GDP were growing more than twice as fast in the 1950s as in the 2000s. At the same time, the average tax rate paid by the top tenth of a percent fell from about 50% to 25% in the last 60 years, while their share of income increased from 4.2% in 1945 to 12.3% before the recession.

Another Day, Another Dollar, Another Bank Busted for Money Laundering

Guess who is about to get nailed for laundering drug cartel money? Why, JPMorgan Chase no less:

JPMorgan Chase & Co's compliance with U.S. anti-money laundering laws is being reviewed by a banking regulator, a source said, making the largest U.S. bank the latest target of a wide investigation of how banks prevent transactions involving drug money and sanctioned countries.

Mortgage Programs Help Those Who Don't Need Help

What a surprise, Reuters outlines how government backed mortgage programs are helping the well off:

Silicon Valley, the birthplace of the microprocessor, the personal computer and the iPhone, is a model of private enterprise at work. But not when it comes to getting a mortgage.

In Santa Clara County, the center of the global tech industry and one of the wealthiest places in the United States, most home buyers get help from the government, an analysis of government lending data shows. The same is true in other wealthy enclaves such as Nassau County, outside New York, and Arlington County, outside Washington, the analysis of more than 50 million loans finds.

It is no secret that the U.S. government propped up the housing market after the financial crisis. What the analysis by Reuters makes clear is the extent to which government programs have helped some of the nation's most well-to-do communities.

IMF Estimates Costs of Financial Regulation

Guess what, they are trivial to the economy and the consumer. In a new study, the IMF estimates the costs of financial regulations. For the United States we have:

We estimate based on a series of calculations that are explained in detail in the paper that in our base case in the long term, U.S. credit prices would rise by about 0.28 percentage points, 28 basis points. This consists of a gross effect of 0.68 percentage points offset by 0.20, 20 basis points of benefits from those lower required returns that investors will demand, 15 basis points of expense reductions, and 5 basis points for some other actions that we explain. If you ignore those offsets as many previous analyses have done, it leads to a significant overstatement of the ultimate impact on consumers and businesses. Outside the U.S. we estimate that even lower net effects will occur on credit pricing, 18 basis points in Europe and 8 basis points in Japan.

Study Shows 800,000 Homeowners Unnecessarily Pushed to Foreclosure

How nice. A new study shows banks could have not foreclosed on 800,000 homeowners:

Just how many more people could have qualified under the administration’s mortgage modification program if the banks had done a better job? In other words, how many people have been pushed toward foreclosure unnecessarily?

A thorough study released last week provides one number, and it’s a big one: about 800,000 homeowners.

The study’s authors — from the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, the government’s Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), Ohio State University, Columbia Business School, and the University of Chicago — arrived at this conclusion by analyzing a vast data set available to the OCC. They wanted to measure the impact of HAMP, the government’s main foreclosure prevention program.

What they found was that certain banks were far better at modifying loans than others. The reasons for the difference, they established, were pretty predictable: The banks that were better at helping homeowners avoid foreclosure had staff who were both more numerous and better trained.

Unfortunately for homeowners, most mortgages are handled by banks that haven’t been properly staffed and thus have modified far fewer loans. If these worse-performing banks had simply modified loans at the same pace as their better performing peers, then HAMP would have produced about 800,000 more modifications. Instead of about 1.2 million modifications by the end of this year, HAMP would have resulted in about 2 million.

More Exposing the Education is a Ticket to the Middle Class Myth

We have more studies popping up showing a college degree does not equal a good job.

In Where Have All the Good Jobs Gone?, Center for Economic and Policy Research economists John Schmitt and Janelle Jones make a simple and powerful point: over the past three decades, the workforce in the United States has gotten a lot more educated and productive, but fewer of us have a good job. The standard that Schmitt and Jones set for a good job is pretty basic: earning the median wage for men of $37,000 a year and having some sort of health insurance and retirement fund at work. Of course, that isn’t a lot of money, and with most workers forced to pick up a bigger share of shrinking health benefits and pensions giving way to 401Ks, not a lofty benefit plan. Which is what makes the results of the study so striking. Even though the typical American worker is twice as likely to have a college degree than 30 years ago, the share of the workforce that has a good job declined, from 27.4 percent to 24.6 percent. The kicker here is that the decline occurred at every education level, although it was worse for those with a scanty education. But even workers with a four-year college degree or better were less likely to have a minimally decent job.

The CEPR researchers take the data a bit further to make two compelling points. If we had not increased our educational level, it would have been a lot worse: only 17 percent of workers would have good jobs. The second point is that if job quality had kept up with increases in education, then 34 percent of workers would have a good job.

Health Care Premiums Hit $15,745

Yoozer, health care insurance costs are just soaring through the roof, as expected, no matter what you think of Obamacare.

It sounds like good news: Annual premiums for job-based family health plans went up only 4 percent this year.

But hang on to your wallets. Premiums averaged $15,745, with employees paying more than $4,300 of that, a glaring reminder that the nation's problem of unaffordable medical care is anything but solved.

The annual employer survey released Tuesday by two major research groups also highlighted another disturbing trend: employees at companies with many low-wage workers pay more money for skimpier insurance than what their counterparts at upscale firms get.

Remember High Frequency Trading?

New York Times profiles two lone wolves of sanity, wanting to put a 50ms time window on trades. This is in essence a 20mph school zone speed limit on the electronic market trading superhighway.

Sal L. Arnuk doesn’t really believe in the tape anymore — at least not in the one most of us see. That tape, he says, doesn’t tell the whole truth.

That might come as a surprise, given that Mr. Arnuk is a professional stockbroker. But suddenly, and improbably, he has emerged as a leading critic of the very market in which he works. He and his business partner, Joseph C. Saluzzi, have become the voice of those plucky souls who try to swim with Wall Street’s sharks without getting devoured.

ON the afternoon of May 6, 2010, shortly before 3 o’clock, the stock market plummeted. In just 15 minutes, the Dow tumbled 600 points — bringing its loss for the day to nearly 1,000. Then, just as fast, and just as inexplicably, it sprang back nearly 600 points, like a bungee jumper.

It was one of the most harrowing moments in Wall Street history. And for many people outside financial circles, it was the first clue as to just how much new technology was changing the nation’s financial markets. The flash crash, a federal report later concluded, “portrayed a market so fragmented and fragile that a single large trade could send stocks into a sudden spiral.” It turned out that a big mutual fund firm had sold an unusually large number of futures contracts, setting off a feedback loop among computers at H.F.T. firms that sent the market into a free fall.

Organic Food Now Big Corporate

The death of the little guy once again as organic gets gobbled up by multinational corporations.

The fact is, organic food has become a wildly lucrative business for Big Food and a premium-price-means-premium-profit section of the grocery store. The industry’s image — contented cows grazing on the green hills of family-owned farms — is mostly pure fantasy. Or rather, pure marketing. Big Food, it turns out, has spawned what might be called Big Organic.

Bear Naked, Wholesome & Hearty, Kashi: all three and more actually belong to the cereals giant Kellogg. Naked Juice? That would be PepsiCo of Pepsi and Fritos fame. And behind the pastoral-sounding Walnut Acres, Health Valley and Spectrum Organics is none other than Hain Celestial, once affiliated with Heinz, the grand old name in ketchup.

Over the last decade, since federal organic standards have come to the fore, giant agri-food corporations like these and others — Coca-Cola, Cargill, ConAgra, General Mills, Kraft and M&M Mars among them — have gobbled up most of the nation’s organic food industry. Pure, locally produced ingredients from small family farms? Not so much anymore.

Local District Attorney's Allowing Debt Collectors to Use Their Names

Thought district attorneys were supposed to keep unscrupulous debt collectors in check? Think again. Naked Capitalism:

It’s one thing for the officialdom to sit back and allow financial services industry chicanery to go un or inadequately punished, quite another to get in bed with them to perpetrate a scam.

The New York Times reports on how over 300 local district attorneys are participating in and profiting from what amounts to a shakedown operation. Let’s say you’ve bounced a check. The debt collectors send letters using the local district attorney’s letterhead, threatening jail time unless you not only pay what is allegedly owed but also an additional fee, typically $150 to $200, to take a “financial accountability” course.

Mind you, the DA has not prosecuted the case, nor even verified that the debt is valid. But the DA’s office winds up getting a cut of the fee from the class that the funds-impaired checkwriter was conned into taking. The debt collectors and the DA call these arrangements “partnerships,” presumably in the Ambrose Bierce sense.

Recent comments