What is happening?

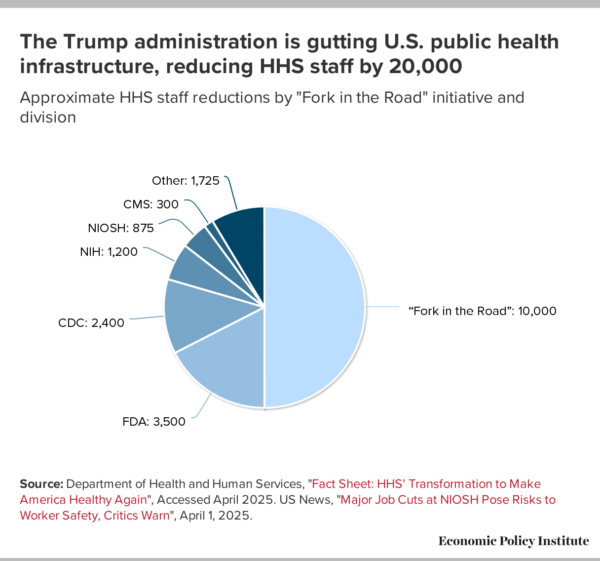

The Trump administration is gutting our national public health infrastructure in real time, setting the stage for the next public health crisis. The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), tasked with “protecting the health of all Americans and providing essential human services, especially for those who are least able to protect themselves,” is set to see a reduction in staff from 82,000 to 62,000 (a decrease of almost 25%) alongside major cuts to spending on contracts.

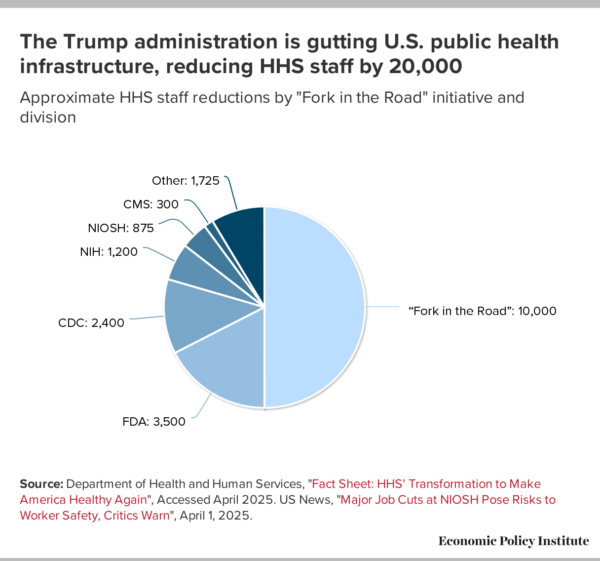

Staff reductions come as the result of induced resignation and early retirement from the “Fork in the Road” initiative set forth by the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), as well as proposed layoffs across several divisions, including the Centers for Disease Control (CDC, 2,400 layoffs), Federal Drug Administration (FDA, 3,500), National Institutes of Health (NIH, 1,200), the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS, 300), and many others.

Figure A

The staff being cut provide critical services that help maintain our public health. CDC generates the information that American communities need to protect and promote their health, prevent disease and injury, and prepare for new health threats (like epidemics and pandemics). The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), a division of CDC specifically dedicated to studying worker health and safety, is facing a staff reduction of two-thirds. The FDA protects the public by ensuring that medical products, drugs, and our food supply are safe to use and consume, as well as providing the public with scientifically grounded health information. NIH is the nation’s medical research agency, with divisions that cover cancer, aging, drug abuse, and mental health, among many other research areas. CMS administers Medicare, Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program, and the Health Insurance Marketplace to beneficiaries.

Why is this happening?

Administration officials like new HHS head RFK Jr. and de facto DOGE head Elon Musk will argue that these cuts to public health infrastructure are intended to reduce waste and increase efficiency. Public health officials disagree; the proposed savings are low compared with the overall government spending ($1.8 billion in proposed cuts compared with a 2025 budget of $1.8 trillion) and such drastic reductions in staff will only inhibit the agencies from doing their work efficiently and effectively if they are able to do the work at all.

There is a better rationale for why the Trump administration wants to dismantle our public health institutions: It favors corporations and employers over workers and the public. This is consistent with the previous Trump administration serving corporations over working people through the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act and with the current Trump administration’s hostility toward workers’ rights. One way dismantling these institutions will benefit corporations at the expense of working families is by reducing the scope for corporate accountability. Institutions like the FDA help set the standards by which businesses are allowed to produce and sell goods and services. The rules and regulations upheld and enforced by these institutions ensure that products that come to market are as safe as possible for public use—and impose a significant cost on corporations that would prefer to get their products to market as soon as possible. Even so, the costs corporations pay in regulatory compliance are far outweighed by the benefits to the public of having safe and healthful products. Any government genuinely concerned with efficiency would recognize that it is more efficient for corporations to pay the costs of meeting regulatory standards than for the public to face illness, injury, and death because of unsafe products.

In addition to providing public health research, institutions like NIH and CDC also help hold corporations accountable by identifying long-term health trends associated with environmental pollution and the use of products and services that have been found to be toxic. CDC’s concerted efforts to identify the harm to public health posed by cigarette usage, including its effects on racial health disparities, are an example of how such research can increase accountability and costs for industry. This research would not exist without public funding, and an administration committed to serving corporate interests at the expense of the public would defund it. Ultimately, making public health research and oversight more difficult by gutting our public health infrastructure will make it easier for corporations to pursue profits without accountability to the public.

Why does this matter for public health?

Gutting these institutions leaves our national public health in a far more precarious position. We are that much more vulnerable to the next epidemic or pandemic when we no longer have the capacity to research, measure, and respond to public health crises. When our ability to disseminate critical public health information—on the efficacy of vaccines, the health consequences of tobacco abuse, and the impact of environmental pollution on health, among other topics—is restricted, this hampers the public’s ability to make sound decisions to promote and preserve their health. When our ability to enforce public health regulations is limited, both within and outside the workplace, workers and their families are at greater risk of exposure to dangerous working conditions, products, and pollution. New obstacles to administering key health care services will mean that fewer low-income families, children, will get the services they need. The result will be a population that is less healthy and less productive.

Why does this matter for racial health disparities?

Research institutions like CDC and NIH created dedicated divisions for studying the causes and consequences of racial health disparities. For example, CDC’s Office of Health Equity and NIH’s National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities have made strides in analyzing racial health disparities and how persistent gaps in health can be eliminated. Yet the Trump administration is eliminating the Office of Health Equity, has placed the director of NIMHD on administrative leave, and is further eliminating CMS’s Office of Minority Health.

These institutions’ research addresses an array of factors related to improving health—including health behaviors, the physical and built environment, and the health care system itself—and has served individuals, families, and communities. It is thanks to research from and funded by institutions like these that we know, for example, the disparate impact COVID-19 had on Black and brown communities throughout the pandemic, due to a combination of their heightened exposure to high-contact work that often lacked necessary PPE, as well as the presence of existing chronic health conditions the disease exacerbated. Targeting these programs and their research for program cuts clearly demonstrates that the Trump administration undervalues the health of minority populations.

What will it mean economically for workers and their families?

Hampering our ability to study, prepare for, and respond to threats to our public health means the next public health crisis will be worse; more people will be sick and more people will die. That hurts the economy as well. The economy produces less when workers and their families are sick or injured; they are less able to show up to work, either due to their own condition or that of a loved one for whom they are providing care, and are less productive when they go to work.

The COVID-19 pandemic sent the economy into a serious economic downturn, with a massive unemployment spike and supply chain disruptions that led to inflation that lasted for years. The previous Trump administration’s uncoordinated response to the pandemic led to countless preventable deaths and unnecessary economic turmoil. Thankfully, Congress met the moment with spending to counteract the downturn and the incoming Biden administration continued that momentum to ensure a relatively swift recovery compared with our peers internationally. Expanded unemployment insurance, tax credits for working families, and anti-poverty measures were all tools that the Biden administration used to secure working families throughout the pandemic; they resulted in an economy that grew the fastest for those at the bottom of the income distribution. The current Trump administration’s dismantling of federal institutions in public health and more broadly suggests that we will not have nearly as many tools to combat the next public health crisis, much less its economic impact.

What should we do about it?

The loss of critical capacity at our public health institutions makes the country more vulnerable to the next public health crisis. Reversing the harm done by the Trump administration, including rehiring staff and reopening closed divisions and programs, will take time. A president and Congress interested in protecting the American people would strengthen our public health infrastructure and invest in research and service provision to prevent, prepare for, or mitigate the next public health crisis.

Rather than dismantling the collective bargaining rights of over a million federal workers, an administration committed to maintaining a healthy nation and economy would recognize workers’ right to organize as essential to improving the nation’s health and well-being and to maintaining a robust democracy. Organized labor has always been at the forefront of lobbying for federal worker protections like the Occupational Safety and Health Act that established NIOSH in 1970. When the FDA was founded at the beginning of the 20th century, it because of public outcry about the meatpacking industry’s unsafe and unsanitary conditions—a clear example of democracy at work. Empowering workers and their families to hold corporations accountable is essential to maintaining our public health and preventing the next public health and economic crises.

Recent comments